At a State Game Commission meeting in Santa Fe earlier this year, Commissioner Robert Espinoza voiced what  many New Mexico hunters have thought but few have said out loud: “Wolves are here to stay.”

many New Mexico hunters have thought but few have said out loud: “Wolves are here to stay.”

For almost 20 years there have been wolves on the landscape in southwest New Mexico, but so few they haven’t had much impact. Now, however, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service appears intent on roughly tripling the number of Mexican wolves in New Mexico and Arizona, while also allowing that population to roam a far greater area.

It’s hard to predict what effect these changes will have on the region’s big game because predator-prey relationships are affected by so many variables. But a review of scientific literature suggests that the proposed increase in wolves likely will not dramatically change things for hunters, elk and mule deer in New Mexico and the Gila region.

Even as the federal proposal moves forward, however, the Department of Game and Fish has filed suit to block further releases of wolves in the wild – a cornerstone of the new plan. The state prevailed in the first round in court, but the Fish and Wildlife Service is likely to appeal in a process that could last years and cost U.S. taxpayers and New Mexico sportsmen and women hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Should the USFWS prevail and the plan be implemented, it would be an important step forward, said New Mexico Wildlife Federation Executive Director Garrett Vene Klasen.

“The endangered Mexican wolf is one of the iconic native species of our state and the entire Southwest, yet there has been a concerted effort to prevent these wolves from taking their rightful place in the landscape,” he said. “A healthy ecosystem needs a full suite of species, including apex predators like the wolf. It is time – in fact, it’s past time – for wolf opponents to get out of the way and let this recovery take root.

“As long as wolves and their impacts on wild ungulates are closely monitored,” he continued, “there is no reason to fear or hamper this reintroduction effort. Conversely, if wolf numbers get out of control, NMWF will support a science-based wolf control program to protect elk, mule deer and other big game.”

The last free-roaming Mexican wolf in New Mexico was reportedly killed in 1942. The species lingered in Arizona and Texas until the 1970s, but a few years later it was estimated that fewer than 50 were left on earth, found in the wild only in northern Mexico. The smallest, rarest, southernmost and most genetically distinct subspecies of all North American gray wolves, the Mexican wolf was listed as an endangered species in 1976. Recovery efforts began soon after.

The reintroduction was mainly a paper exercise until 1998 when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released 11 wolves into the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, which includes all of the Apache and Gila National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico. About three-fourths of the recovery area is in New Mexico.

Since then dozens more wolves have been released and those wolves have reproduced, but the effort has hardly been a roaring success. After two decades, the population in 2016 is estimated at roughly 100, about half of them in New Mexico.

Experts had expected to see that many wolves a full decade earlier – by 2006 – but a combination of factors has held the population back, including poaching, vehicle kills and the removal of problem wolves by the Fish and Wildlife Service itself. Wolves can be trapped or killed if they pose a threat to humans or even wander off their reservation.

Now, however, the Mexican wolf is poised for a population boom – if politics, ideology and litigation allow. The Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed to revise its wolf recovery plan to remove many of the barriers that have constrained the population’s growth. Under the agency’s preferred alternative, over the next 12 years:

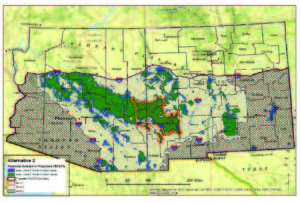

- Wolves would be allowed to inhabit a much larger geographical area than now – from I-40 south to the Mexico border across both New Mexico and Arizona;

- Wolves could be released in more area than currently allowed, essentially “seeding” new areas;

- Wolves would be allowed to migrate into the U.S. from Mexico;

- Landowners, tribes and wildlife management agencies would have greater latitude in controlling problem wolves;

- State wildlife managers could remove wolves in areas where biologists believe the elk and mule deer depredation is unacceptably high.

Under its preferred alternative, USFWS wants to see 300 to 325 wolves in an area that spans more than 150,000 square miles. In contrast, today there are fewer than 100 wolves spread over 9,500 square miles.

No one can predict exactly how such an increase in Mexican wolf numbers would affect elk, mule deer and hunters in the Gila region, in part because predator/prey relationships are constantly changing. The Fish and Wildlife Service puts it this way: “The relationships between carnivores and other species, and the dynamic ecosystems in which they live, could be the most poorly understood and controversial dimension of carnivore ecology.”

Substantial research has been done on the reintroduction of Yellowstone-area wolves and their role in declining elk numbers in that region. Because of the complexity of predator-prey relationships, however, even some researchers disagree on the results. And some of the work might surprise hunters. For example, one study found that wolves didn’t cause the Yellowstone elk decline – grizzly bears did, through high predation of calves. Another study found that grizzlies were killing more elk calves than in the past because their historic main prey at certain times of year – cutthroat trout – had dropped precipitously. Why? A third study found the cutthroat decline based on illegally released and rapidly proliferating lake trout.

The Fish and Wildlife Service environmental impact statement on its new Mexican wolf plan doesn’t cite specific studies from the Southwest regarding the likely effect of wolves on elk, but notes that “At statewide scales, wolves are expected to have little or no effect on the abundance of elk and deer across most of Arizona and New Mexico ….”

That’s based largely on reports to date from the New Mexico and Arizona game departments and the White Mountain Apache tribe. But an earlier report does look specifically at the wolf-elk relationship in New Mexico. Compiled by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish during the early days of the wolf program, it suggests that hunters probably don’t have much to fear.

The report was prepared in 2004 by the department’s Elk Program Manager at the time, Steve Kohlmann, who has since left Game and Fish and now has a wildlife consulting business in California. Titled “Evaluating the Relationship between Mexican Wolf Recovery, Elk Populations and Associated Hunting Opportunities in New Mexico,” Kohlmann’s report paints a substantially different picture of wolves and elk than many hunters imagine.

When the report was written, Game and Fish estimated the Gila region elk population at 18,000 to 22,000, while the total wolf population was around 50 – half the size it is now.

Mexican wolves are the smallest of the gray wolves, weighing 60 to 90 pounds, whereas a male Yellowstone wolf can weigh 180 pounds, and females can reach 120. Relying on models developed by other biologists working on wolf diets and predation patterns, Kohlmann estimated that a Mexican wolf requires from three to 11 elk per year, or an average of about six.

That’s a conservative assumption, he noted, because wolves are also likely to prey on mule deer, rabbits and other small game. One collared wolf was found to eat carp. But an analysis by the Arizona Department of Game and Fish says that elk makes up about 75 percent of Mexican wolves’ diet. Another 11 percent is small mammals and unknown sources, 10 percent is deer and 4 percent is livestock.

But for the sake of argument, assume that elk make up 100 percent of wolves’ diet. Because elk numbers are limited by the carrying capacity of the region, Kohlmann’s work – again, based on peer-reviewed research by others – predicted that if the two species were essentially on their own, they would come into equilibrium at about 200-250 wolves while the Gila elk population would remain fairly steady at around 18,000. In other words, wolves would not kill every last elk.

Kohlmann also modeled what might happen if there were no wolves and the only predation was by humans. His work suggested that humans could harvest about 26 percent of the total Gila elk population every year, or about 4,100 animals – well above the current levels – and elk numbers would remain steady. In contrast, hunters in 2014 took 2,046 elk from the greater Gila herd.

(A separate study, by Eberhardt et al. in 2007, states that predation by wolves likely has a much lower overall impact on ungulate populations than does antlerless harvest by hunters.)

In a third model, Kohlmann blended the two scenarios and found that elk numbers could remain steady if the total combined harvest by wolves and humans was limited to about 26 percent of the elk population per year. Again, that’s assuming each wolf requires six to seven elk per year and hunters continue to harvest at historical rates. If it turned out that Mexican wolves need 10 or more elk per year, he noted, the elk population would start to decline.

The bottom line, he found, is that the Gila elk population should continue to thrive, even with sustained hunting pressure and increasing the number of wolves to 200 to 250.

“The model shows that we can harvest the elk population, but that the sum of the human harvest and wolf kill cannot exceed the annual growth rate,” Kohlmann wrote. “In general, I have found that 26 percent combined kill is about all the elk population can tolerate. How we allocate is now the manager’s problem.”

And of course, any model is only as good as the data used to build it. Better information about wolf habits, diet and territory requirements would strengthen the model, Kohlmann wrote.

It isn’t clear, for example, how elk will respond as wolf predation grows. “They could disperse more into habitats where they are less vulnerable, thereby reducing predation rates,” his NMDGF report said. That, in turn, could affect land use issues such as elk damage or hunter success and satisfaction.

Also unclear is how the elk population would change in terms of age and sex ratios if wolves prey selectively – targeting vulnerable younger or older animals rather than, say, healthy bulls and cows. “That could potentially have an impact on the recruitment and growth rate of the population.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposal doesn’t answer any of those questions. But the proposal itself – a three-fold increase in the number of wolves paired with a 15-fold increase in their area – suggests that pressure on Gila elk is not likely to increase, and could in fact decrease.

Beyond their effect on elk and deer, wolves could have a beneficial impact on other species and habitat. In the Yellowstone region, for example, research has shown improvements in riparian habitat and wildlife after wolves returned. Because elk no longer linger alongside streams, the willows and other shrubs come back into balance, which has led to more beavers and overall watershed health. Coyote numbers have declined in places where wolves have come back, according to some reports, because wolves kill them as competitors for scavenging the carcasses of dead animals.

The federal Endangered Species Act requires the Secretary of the Interior to implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of endangered species. Yet after nearly 20 years of reintroduction efforts, the Mexican wolf population is stuck in neutral. The new plan should make a huge difference, the USFWS says, simply by giving them more room.

“A larger population of wolves distributed over a larger area has a higher probability of persistence than a small population in a small area,” the agency’s environmental impact statement says.

In addition, more animals in the wild will mean less inbreeding and an overall healthier population, both of which will help the species persist.

In the early days of the wolf reintroduction effort, then-Gov. Bill Richardson was a supporter of the program, as was his Game Commission and the Department of Game and Fish. New Mexico had a seat at the management table, alongside the federal agency and Arizona. That changed when Gov. Susana Martinez was elected in 2010. Since then, her appointed State Game Commission – which dictates the Game Department’s stance – appears to be doing whatever it can to stymie the reintroduction.

Ironically, by leaving the planning table during the wolf recovery plan, the Commission essentially muted the Department’s voice on recovery numbers and the extended range of the project.

Last year, the Department refused to renew two longstanding permits used in the reintroduction effort: one, for the Service to release more wolves on federal land, and another allowing the Turner Endangered Species Fund to hold wolf pups temporarily on the Ladder Ranch before they were released. The Game Commission upheld both decisions.

The Game Commission has repeatedly cited the lack of a new recovery plan as its rationale for rejecting the permits, and has chided the Fish and Wildlife Service for foot-dragging. In late April, however, New Mexico refused to sign onto a proposed settlement to a lawsuit, brought against FWS by wildlife advocacy groups and the Four Corners states, that commits FWS to having a revised plan completed by Nov. 30, 2017. A Game Department spokesman told the Albuquerque Journal that New Mexico refused to sign because of “the overly aggressive time frame [the settlement] specifies.”

Meanwhile, the feds released two wolf pups in April, saying that their action upholding the federal Endangered Species Act trumps the state’s decision to withhold its permits. That prompted Game and Fish to file its lawsuit to stop further releases and to have the feds recapture the two pups.

A federal judge in mid-June granted the state a temporary injunction against further releases, though he declined to order FWS to retrieve the pups. The feds are likely to appeal. As court costs build, this case could end up costing hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees, which U.S. taxpayers and New Mexico sportsmen and women will end up paying.

“In the end,” Vene Klasen said, “what we have is our Department of Game and Fish – which is mandated by state law to restore Mexican wolves – dragging its feet and refusing to help get an animal off both the state and federal endangered species lists. This is politics interfering with science and wildlife management. It is the exact opposite of what the North American Model of Wildlife Management tells us. That it’s costing us tens of thousands of dollars just makes it worse.

He continued: “Restoring threatened and endangered native species is not an a la carte menu for the Department to choose from based on the personal biases of the Governor, her Commission or the Department’s directorate. The state’s wildlife management mandate is simply not set up this way. The precedent this sets is truly disturbing.”