By BEN NEARY

NMWF Conservation Director

Cochiti Pueblo’s long-running blockade of U.S. Forest Service roads that cross a parcel of former state trust land has prompted a group of private landowners who own inholdings in the forest to sue Sandoval County, alleging it has failed in its duty to keep public rights of way open.

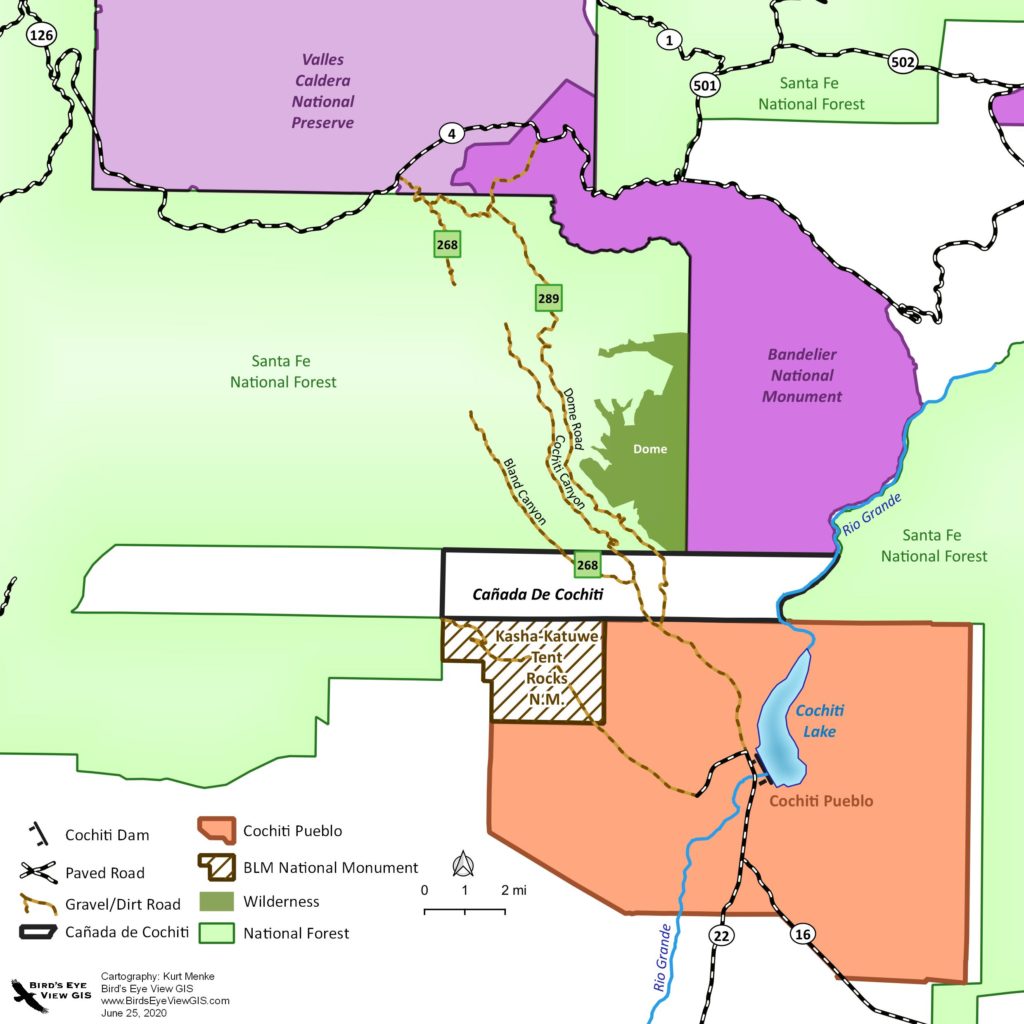

Cochiti Pueblo closed Forest Road 289 – commonly called the Dome Road – in late 2018. It runs from the Cochiti area northwest through a parcel of pueblo land, then through forest service land before joining NM 4 near the Valles Caldera.

Closing the Dome Road, along with the closure of other nearby routes that lead to forest service lands, has left some landowners unable to reach their private inholdings within the Santa Fe National Forest. The closures also have blocked the general public, including Native Americans from other neighboring pueblos, from following traditional routes into the forest for hunting, wood-cutting, tending to livestock and general recreation.

The only people apparently fighting the closures are landowner Hugh Martin and a few others who own forest inholdings in the area.

Martin and the others have a lawsuit pending in state district court in Sandoval County. They’re asserting that the county owes them damages for failing to stick up for the public easements across the former state parcel that the pueblo acquired. In the alternative, they’re asking the court to ratify their property rights and order the county and the pueblo not to interfere with their access.

“It’s the only legitimate access into that area.” Martin said of the roads Cochiti Pueblo has closed. “It’s historic access. It’s always been there since that whole area was developed. So yeah, absolutely it affects us. We can’t access our properties, and neither can any of our other friends and people we know. Absolutely it affects us, and absolutely it’s an illegitimate, illegal move by the Cochitis to shut the gate off.”

Attempts to reach Cochiti Pueblo officials for comment were unsuccessful. An attorney for the pueblo declined comment.

Cochiti Pueblo has maintained barriers to the roads on a parcel of land it obtained in a 2016 land exchange agreement with the New Mexico State Land Office.

Cochiti Pueblo obtained the 9,270 acres of former state trust land in 2016 by swapping a hotel it had purchased in downtown Santa Fe — Garrett’s Desert Inn on Old Santa Fe Trail – to the state. The land parcel the pueblo acquired, immediately north of the old pueblo boundary, is called “Cañada de Cochiti.”

In the transfer documents, Cochiti Pueblo and the State Land Office agreed that Sandoval County would retain public rights of way over the Cañada de Cochiti parcel to the Dome Lookout road, the Bland Road, the Rancho de Cañada Road and the Dixon’s Apple Road, “for so long as they are maintained as public roads.”

Some roadways in the area have been closed since fire and flooding in the area in 2011. However, the Dome Road (Forest Road 289), which connects with NM 4 in the Valles Caldera, had remained open aside from wintertime closures until the pueblo blocked it in late 2018.

On Sept. 4, 2019, Cochiti Pueblo filed a document in the Sandoval County Clerk’s Office which it titled, “Cancellation of right-of-way easement….” regarding Forest Road 268 — the Bland Canyon Road — and (Forest Road 89) “Rancho de la Cañada Road,” which runs up Cochiti Canyon.

The pueblo’s document states that the cancellation of the rights of way was based on Sandoval County’s “failure to comply with express covenants” of the State Land Office transfer agreement in regard to the roads.

Cochiti Pueblo applied to the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs in late 2016 to take the Cañada de Cochiti parcel into trust for the pueblo, a move that would make it legally “Indian Country.”

In that trust application, which is still pending, and supporting documents, the pueblo has assured federal officials that taking the land into trust would present no land management problems. The pueblo stated in its trust application that the property was subject to road easement rights of way issued to Sandoval County.

Federal action to take the land into trust would offer benefits to Cochiti Pueblo. Trust land is governed by tribes and generally not subject to state laws or taxes, though federal restrictions may still apply. Certain federal programs and services are only available on trust lands.

In recent weeks, the Cerro Pelado Fire has burned down the eastern slopes of the Jemez Mountains into the Cañada de Cochiti parcel. Firefighters have staged in the area and helicopters have scooped up water at Cochiti Lake to dump on the blaze. Firefighters have used the Dome Road to battle the blaze but it has remained closed to the public.

Cochiti Pueblo Gov. Phillip Quintana and Lt. Gov. Dave Gordon addressed the public at a U.S. Forest Service briefing on May 1 on efforts to fight the fire. They gave a description of land conditions and the pueblo’s perspective of the road closures.

“Cochiti Canyon, there’s no way to pass through there,” Quintana said at the briefing. “The road is no longer there. Where it comes out of the canyon, where the apple orchard was, that’s it. That’s all you can go driving, and barely walking. Past that, into the canyon, all you’ll see is these ponderosa pines just lining the bottom of the river bed in that area. There’s no way anybody can go past, or get access into Cochiti Canyon.

“The same way with Bland (Canyon),” Quintana said. “Bland is all blocked through there. It’s the same thing, all the debris. We’re talking trees of good size just looking like toothpicks all across the riverbed. So again, that’s as far as we can go, or even firefighters can go.”

Quintana emphasized that the area is of critical importance to the pueblo people.

“That is our land, we’re trying to get it into trust for us,” Quintana said. “We had to buy our own land back. We spent $8 million getting our own land back. That’s shameful, I think. That’s how long we’ve been after it.”

Lt. Gov. Gordon told the crowd that the pueblo had opened access for fire crews on the Dome Road. “We’re working closely with the forest department, because right after our land is Santa Fe National Forest, and that road is in need of tremendous repair, tremendous work, in that area as well.

“In the future, I”m sure that once we get the land into trust, that the pueblo will allow access through our land into Santa Fe National Forest,” Gordon said. “But right now, we have to be patient.

“We’ve been trying to get our land into trust for, it’s been about eight years now,” Gordon said. “And we’re planning a trip now to Washington to talk with (U.S. Secretary of Interior) Debra Haaland. She is going to help us, and we’re going to try to expedite.”

Gordon said tribal members haven’t been able to go into the closed area. “None of our tribal members can go in there and hunt, or get wood, do any of that kind of stuff, because if we do, we jeopardize our chances of getting it into trust,” he said.

In November 2016, then Cochiti Gov. Nicholas F. Garcia wrote to John E. Antonio, Sr., superintendent of the BIA’s Southern Regional Office in Albuquerque. “Placing these lands in trust will not result in any major jurisdictional problems or conflicts in land use within Sandoval County,” Garcia wrote.

Among the documents that the BIA turned over to the NMWF in response to its request under the federal Freedom of Information Act was a March 2017 letter from David C. Mann, then general counsel with the state’s Indian Affairs Department. He informed the BIA that the state opposed the pueblo’s application to have the federal government take the parcel into trust.

“The state observes that action by the United States to take the subject property into federal trust could essentially deprive easement holders of their property rights, including Sandoval County and the Qwest Corporation, who retain easements on the subject property,” Mann wrote.

Mann cited a 2016 federal court ruling in which a judge held that tribal sovereignty barred action to enforce an easement that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management had over a parcel of land that the federal government had taken into trust for San Felipe Pueblo.

C. Bryant Rogers, lawyer for the Pueblo, wrote to Antonio at the BIA disputing Mann’s comment. Rogers said placing the Cañada de Cochiti parcel into trust wouldn’t change the fact that the pueblo enjoys sovereign immunity – meaning generally that it’s not subject to being sued without its consent. Rogers said that status would be the same whether the pueblo merely owns the parcel or if the federal government takes it into trust.

Rogers told Antonio that even once the federal government took the land into trust, anyone holding a private right of way in the area would still be able to seek relief in federal court against tribal officials or employees who unlawfully blocked access.

Rogers recently declined to speak with the NMWF about the situation, saying he would need permission from the pueblo.

Joseph Romero runs a small grocery store in Peña Blanca. He has said he’s invested nearly half his net worth in 22 acres in Cochiti Canyon, where he had built a cabin that later burned down.

“It’s been disastrous for me,” Romero said recently of the pueblo’s closure of roads in the area, including blocking the road to Cochiti Canyon. “The fire 11 years ago now, the Las Conchas Fire, burned down the cabin that I had just finished up there. Then the flood wiped out the road and Cochiti closed access.”

Romero said it’s been frustrating to lose access to his land.

“I own about 22 acres up there,” he said. “It has four springs on the property. It was a piece of heaven before the fire. I haven’t been up there since. I’ve seen pictures, but that’s about it.”

Romero said he hasn’t heard anything from pueblo officials about the closures, but said he believes they should respect rights of way that were established over the parcel before the pueblo got it from the state.

“They ought to honor their commitments,” Romero said of the Cochiti Pueblo. “They signed easements in perpetuity for all those roads.”

Romero said more people need to hear about Cochiti Pueblo’s actions and demand action from state and federal officials. “That’s really the only hope we have,” he said, “that people get outraged about this type of behavior.”

State and federal officials generally are closed-mouthed about any efforts to reopen the roads or otherwise address the situation with Cochiti Pueblo.

Sandoval County Manager Wayne Johnson referred questions to the county’s information office, which didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Officials with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs declined comment and only provided information to the New Mexico Wildlife Federation in response to a formal request under the Federal Freedom of Information Act.

Brian Riley, Jemez District ranger on the Santa Fe National Forest, said recently that his agency is still trying to work with the pueblo to open the Dome Road.

“It’s been passed to Forest Service attorneys, but other than that, there’s really no comment. We’re still trying to get it open, that’s all I can say,” Riley said.

A call to the public information office at the Santa Fe National Forest headquarters seeking information about the closure didn’t prompt a response from the agency.

Martin and other landowners filed their lawsuit against Sandoval County in April 2021. Presiding District Judge Christopher Perez this spring granted Sandoval County’s request to require Martin and the other landowners to bring Cochiti Pueblo into the case as an indispensable party.

In response, Rogers recently filed notice with Perez that Cochiti Pueblo won’t waive its tribal sovereignty and did not agree to be sued in state court. Perez has scheduled a pretrial conference on the case for June 3.

In a recent interview, Martin said he and other landowners are incensed that Cochiti Pueblo’s actions are preventing them from reaching their property.

“The tribes are out of control with this issue,” Martin said, adding that the state’s congressional delegation and federal agencies don’t want to touch the issue.

“Absolutely, we’re pissed off as hell,” Martin said. “We’re tired of it. We know it’s illegal. We’ve got no help from the Forest Service, we’ve got no help from BLM, we’ve got no help from BIA, of course. Certainly the Cochiti Pueblo’s completely hostile. Sandoval County, I think they tried to step in, and they were very good initially in trying to get us access.”

Sandoval County sent a road crew into the area after the 2011 flooding to try to repair damage to the roads, Martin said. The lawsuit states that Cochiti Pueblo arrested the county road crew and threatened to continue to arrest any county officials who came onto the property

Martin said he believes state and federal officials are treating the pueblo with kid gloves. “I think it’s clearly illegal, clearly they don’t have the right to do it, and simply nobody wants to call them on it, and say, ‘no, this is nonsense, I don’t care if you’re indigenous people or not. Clearly this is wrong, it’s illegal. Stand down.’”

The New Mexico State Legislature in 1997 urged the federal government to recognize Forest Road 268, the “Bland Canyon Road” as a historic trail. The resolution passed by the Legislature said New Mexicans had used it to travel between the Rio Grande Valley and the Valles Caldera in the Jemez for centuries and that it was important throughout New Mexico history for the movement of livestock, and to allow residents — Indians and non-Indians alike — to reach the forest and to cut wood and hunt.

Lawyer A. Blair Dunn represents Martin and the other landowners in their lawsuit against Sandoval County. His father, former State Land Commissioner Aubrey Dunn, signed the trade agreement with Cochiti that gave them the Cañada de Cochiti parcel in exchange for the Santa Fe hotel property.

“The pueblo agreed to take that property from the land office subject to the rights-of-way easements,” lawyer Dunn said. “They don’t really have any authority, that’s not actually trust land yet. It’s still outside of trust. The pueblo’s idea that they can just come in and tell everybody what to do, because, ‘hey, we’re the pueblo and Indian law says we win.’ That’s essentially what they’ve done here.“

Dunn said Sandoval County can’t close a road without going through that legal process. He said the county has shied away from conflict with the pueblo since pueblo police arrested the county road crew. “And so, we turned around and said, ‘well, you’re giving them what they want, so you break it, you bought it,’ essentially.”

Dunn said he doesn’t expect the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs will move on Cochiti Pueblo’s application to bring the property into trust until the lawsuit over the easement issue is resolved.

“There is now a cloud ultimately on that title,” Dunn said. “And so BIA traditionally, with a property like this that has an easement like this in dispute over it, they won’t put it into trust until all of the issues have been resolved. So I think this is probably going to hold that up until we get that sorted out in this lawsuit.”

Dunn said he regards reopening the roads as an important issue for the general public as well as to his clients.

“My focus of course for my clients is getting them back to their in-holding properties,” Dunn said. “But this is a pretty important road to access some very pretty country that people on the national forest should be able to access.”

Dunn also said he believes the state government should be stepping up. “I think that certainly the state should be coming in because they’re the ones that made the conveyance to the pueblo,” he said.