From the Kiowa National Grasslands and wide-open prairies of Union and Colfax Counties in far northeastern New Mexico to the scenic vistas of the Gila Wilderness in the far southwest, sportsmen conservation runs deep within New Mexico’s history and identity. At the heart of this history and shaping the ethic of sportsmen conservation were two of the nation’s most prolific hunters, Earnest Thompson Seton and Aldo Leopold, whose mystical encounters with New Mexico’s native wildlife forever changed them and the nation’s understanding of conservation.

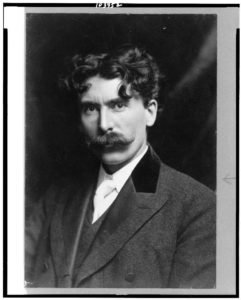

Earnest Thompson Seton

Earnest Thompson Seton first arrived in New Mexico in 1893 in pursuit of a wolf that would forever change him and the way the world understood wildlife. Although Seton had been born in England in 1860 and raised in Canada, Seton’s heart lay in the American West. Shortly after his 21st birthday, Seton moved to the United States to further his career as a naturalist, writer and artist. By the age of 33, Seton had nationally established himself as a widely sought-after bounty hunter and trapper. Seeking to fulfill a bounty on wolves and coyotes put out by a New Mexico rancher, Seton traveled to Clayton in October 1893 in pursuit of a formidable opponent, a legendary wolf known as “Lobo, the King of the Currumpaw,” (an area west of Clayton near Capulin Volcano National Monument).

Although Seton had an expansive reputation as a wolf hunter, which had derived largely from hunting Timberwolves in Canada, New Mexico’s locals were dubious of an outsider’s ability to track and hunt Lobo, who had wreaked havoc on Anglo and Hispanic ranchers for years. In the fall of 1893, Seton’s journal noted that everyone had heard of the notorious Lobo, the leader of a remarkable pack of native gray wolves and who was “a giant among wolves, and was cunning and strong in proportion to his size” Although an expert tracker, Seton quickly found himself outmatched by Lobo, who was as elusive as a ghost and impervious to conventional hunting and trapping techniques.

After repeated failure and with his reputation on the line, Seton turned to “trickery and treachery against an animal whose weaknesses were loyalty and fidelity.” Although he was yet to lay eyes on the legendary wolf, Seton observed smaller wolf tracks running ahead of the pack leader, tracks he attributed to Blanca, a white wolf known to be Lobo’s mate. Recognizing Blanca as Lobo’s weakness, Seton set traps for Blanca. Finally, in January 1864, Seton successfully trapped Blanca, who he found whining in a trap with Lobo by her side. As Seton approached, Lobo ran to a safe distance to watch Seton and his men kill Blanca. Seton dragged Blanca back to his ranch house leaving a scent trail to lure in Lobo. For two days, Lobo was heard howling in the distance and Seton described the haunting howl as having “an unmistakable note of sorrow in it…no longer the loud, defiant howl, but a long, plaintive wail.”

With fierce loyalty, Lobo followed Blanca’s scent trail to Seton’s house where the hunter had traps set for him. On January 31st, 1894, Lobo, with each of his four legs clutched in a trap, was caught. Despite severe injuries, Lobo stood and howled when Seton approached. Moved by the wolf’s bravery and loyalty, Seton removed Lobo from the traps and took him to his house. Sitting next to the dying Lobo Seton noted:

Poor old hero, he had never ceased to search for his darling…I set meat and water beside him, but he paid no heed. He lay calmly on his breast and gazed with those steadfast yellow eyes away past me down through the gateway of the cañon, over the open plains—his plains—nor moved a muscle when I touched him…A lion shorn of his strength, an eagle robbed of his freedom, or a dove bereft of his mate, all die, it is said, of a broken heart…this only I know, that when the morning dawned, he was lying there still in his position of calm repose, his body unwounded, but his Spirit was gone—the old King-wolf was dead.

In 1894, Scribners Magazine published Seton’s story on Lobo, which became a national bestseller. The story of Lobo, proved more powerful than Seton could have guessed to both the author and audience as it began to open the eyes and consciousness of America to the inherent value of wildlife and what it could teach us. Speaking to this, scholar Andrew Isenberg notes:

Seton reflected the perspective of the nineteenth century, which sought the destruction of most wildlife, particularly predators, in order to domesticate the environment: he unapologetically killed Lobo and Blanca in order to protect the Currumpaw livestock. Yet, his characterization of Lobo and his pack heralded a new representation of wildlife. Seton’s animals inhabit a moral universe of honor, love, and choice. Seton regards Lobo not as a varmint but as a worthy adversary.

As Seton scholar David Witt notes, “Seton came away from New Mexico with more than just blood on his hands. His contention that animals are related to humans in a moral sense would soon lead him to the logical conclusion that we are therefore responsible for their preservation.”

Aldo Leopold

Following in Seton’s footsteps in New Mexico was a young ambitious forester and ecologist named Aldo Leopold. Born in Iowa in 1887, Leopold also developed an interest in the natural world from a young age and spent hours writing about his surroundings and reading outdoor adventures, including the works of Seton. In 1909, Leopold graduated from the Yale School of Forestry, where he had heard Seton as a guest lecturer, to pursue a career with the newly established U.S. Forest Service in Arizona and New Mexico.

Seeking to appease local ranchers and hunters who viewed predators as a nuisance and competition, Leopold was assigned to hunt and kill bears, wolves, and mountain lions throughout the southwest. As an expert marksman with a bow and rifle, Leopold was a natural born hunter who believed it was his duty to wage a “steady war” on these predators in order to domesticate the Wild West. However, like Seton it was an experience with one of New Mexico’s wolves that forever changed Leopold’s thinking about humanity’s relationship to nature. While leading his forestry crew on a mission near the New Mexico/Arizona border, Leopold spotted a wolf and her pups crossing a river. Leopold shot into the pack and scrambled down the mountain to see what damage he had done. A pup and the mother lay wounded and the protective mother snapped and growled when Leopold approached. Watching the wolf die, Leopold later wrote:

In those days we never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack, but with more excitement than accuracy…We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean a hunters’ paradise. But seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

In those days we never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack, but with more excitement than accuracy…We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean a hunters’ paradise. But seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

Like Seton’s experience with Lobo, watching the green fire die in the wolf’s eyes began to slowly transform Leopold in ways that would forever change him and the nation’s understanding of conservation.

The Transformation of Seton and Leopold

While the hunt of Lobo and the green fire experience served as significant turning points in the lives of Seton and Leopold, it would take years for both men to internalize and articulate what these experiences meant to them and what they required of humanity. In 1907, while hunting in the Artic, Seton came across a lynx that he had shot. In a moment of transformation, Seton noted:

It sounds all right and clear, but to this day I cannot forget the kitten-like wonder of those big, mild eyes, turn on me as I fired. He fell without a sound, and when I came up, he still gazed without a moan, without a sign of resentment, with nothing but pained surprise, which my conscience translated into: ‘So this is your love of wild things.’

As David Witt notes, through this mystical encounter and continued transformation, Seton “had at last fully internalized the meaning of Lobo’s death. After his return from the Artic, he dedicated himself almost fully to the cause of wildlife conservation” and outdoor youth education.

Like Seton, Leopold’s transformation was slow and subtle. In 1912, Leopold was promoted to the supervisor of the Carson National Forest in northern New Mexico. While awaiting this assignment, Leopold had met an attractive girl from Santa Fe, Estella Luna Bergere, whose prominent Hispanic lineage dated to early Spanish shepherds and was deeply rooted in New Mexico’s land. As the love of Leopold’s life, Estella’s New Mexico Hispanic culture and traditions played a strong role in their relationship. Each night the family would gather around a songbook written by Estella to sing traditional songs in Spanish about the land and her Hispanic culture and values. New Mexico’s Hispanic culture, heritage, traditions and land ethics began to shape Leopold and his understanding of conservation. As Leopold’s transformation continued, he developed an ecological ethic that replaced his earlier perspective, which stressed the need for human dominance. He also began to rethink the importance of predators in the balance of nature. Reflecting on this, Leopold noted:

Since then I have lived to see state after state extirpate its wolves. I have watched the face of many a newly wolfless mountain, and seen the south-facing slopes wrinkle with a maze of new deer trails. I have seen every edible bush and seedling browsed, first to anemic desuetude, and then to death. I have seen every edible tree defoliated to the height of a saddlehorn. Such a mountain looks as if someone had given God a new pruning shears, and forbidden Him all other exercise. In the end the starved bones of the hoped-for deer herd, dead of its own too-much, bleach with the bones of the dead sage, or molder under the high-lined junipers … So also with cows. The cowman who cleans his range of wolves does not realize that he is taking over the wolf’s job of trimming the herd to fit the change. He has not learned to think like a mountain. Hence we have dustbowls, and rivers washing the future into the sea.

Synergizing the transformative wolf experiences of both Seton and Leopold, Andrew Isenburg further explains:

Seton’s wolf Lobo was a bandit…doomed to be destroyed by the inevitable progression of the laws of property and profit. By contrast, Leopold’s wolf was, like Leopold himself, a kind of forest ranger, enforcing the moral ecology of wildlife…it is hard to imagine Leopold’s wolf, with the ‘fierce green fire’ in her eyes, without the precedent of Seton’s lobo. Seton made wolf ecology a world of conscience and reason; Leopold invested that world with moral purpose.

Seton and Leopold’s Lasting Legacy on New Mexico and Conservation

It is difficult to capture the vast legacy of Earnest Thompson Seton and Aldo Leopold and their impacts on New Mexico and conservation. Yet, one of the greatest impacts of these two sportsmen was changing the way America understood conservation, land, water and wildlife.

Earnest Thompson Seton sought to change America’s consciousness about wildlife and was one of the first people to write about the science of animal behavior and the importance of conserving wildlife. Through his writings and sketches, Seton challenged humanity to be more contemplative and intentional in the way we approach nature and our relationship with it. Seton believed in Charles Darwin’s principal that humanity is an integral part of nature and we must be conscious of what we are doing and how it impacts nature. Seton believed that if humans are going to be hunters, fishermen, timber harvesters, cattle growers or nature users, then we have a moral obligation to work and recreate with intentionality. Seton concluded we must be mindful of how we use natural resources and the implications of our actions on the present and future. We cannot solely make decisions impacting land, water and wildlife based on utilitarian principals, but must base such decisions in morality and long-term thinking.

Another major contribution Seton made was his understanding of the importance of protecting wildlife corridors and connectivity. While in the Artic in 1911, Seton observed hundreds of antelope lodged against a fence built by the Canadian Pacific Railroad blocking the antelope from reaching their summer range. Watching massive herds of antelope die, over 100 years ago Seton recognized the importance of protecting wildlife movement and that if corridors are not protected from mindless human development it can lead to the demise of a whole species. Recognizing the wisdom and science behind Seton’s perspective, the New Mexico Wildlife Federation is actively engaged in working with federal and state agencies, native tribes, and private landowners to identify corridors and protect wildlife connectivity.

Expanding upon Seton’s perspectives and creating his own ethical framework, Aldo Leopold developed what became known as the “Land Ethic.” Reflecting on his time in New Mexico and writing as a Professor at the University of Wisconsin, Leopold articulated this new ethic boldly proclaiming, “we abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” Coupling this ethical perspective with science, Leopold became a pioneer in both game and land management. In calling for us to ‘Think like a Mountain’ and deepen our understanding of the interconnected relationship we have with the land and with each other, Leopold also reminded us that we are to “examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

The impacts of Seton and Leopold on New Mexico and conservation cannot be understated. Following his trip to New Mexico and believing deeply in educating youth about conservation and the outdoors, Seton, formed the Woodcraft League, whose teachings were rooted in Native American wisdom, crafts and traditions and would ultimately result in Seton becoming a founder of the Boy Scouts of America. Philmont Scout Ranch near Cimarron now houses the Seton Memorial Library and since it’s opening more than 1 million scouts and leaders have experienced the outdoor education offered through the Ranch. Early in the 1900s, Seton also became one of the first Anglo defenders of Native rights, culture, and tribal values. In 1930, Seton bought 2,000 acres of land outside of Santa Fe, now known as Seton Village. Today Seton Village is home to the Academy for the Love of Learning, housing the Seton Legacy Project, which includes a gallery containing Seton’s writings and art and focuses on the connection between Seton’s teachings and contemporary environmental issues.

As a forest superintendent, Aldo Leopold moved the headquarters of the Carson National Forest from Colorado to Tres Piedras, New Mexico, where his and Estella’s cabin (‘mi casita’) remains and houses an annual writer in residence program focusing on applying Leopold’s teachings to modern environmental issues. In 1914, Aldo Leopold formed the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, a sportsmen organization whose mission for the past hundred years has been to inspire New Mexicans to conserve public lands, watersheds, and wildlife for our children’s future. In 1924, Aldo Leopold was instrumental in developing a landmark proposal to make the Gila National Forest the nation’s first Wilderness area. While Leopold’s ecological legacy shaped land and game management across the country, Leopold’s teaching on conservation continues to shape children throughout the nation including at schools like the Aldo Leopold Charter School in Silver City.